One doctor accidentally chopped off part of a newborn’s left index finger during a delivery. He also attacked two nurses who vividly described how he choked them while in a rage.

Another doctor drained the wrong side of a patient’s chest while attempting to remove a mass of fluid and altered a medical record to show that he operated on the correct side.

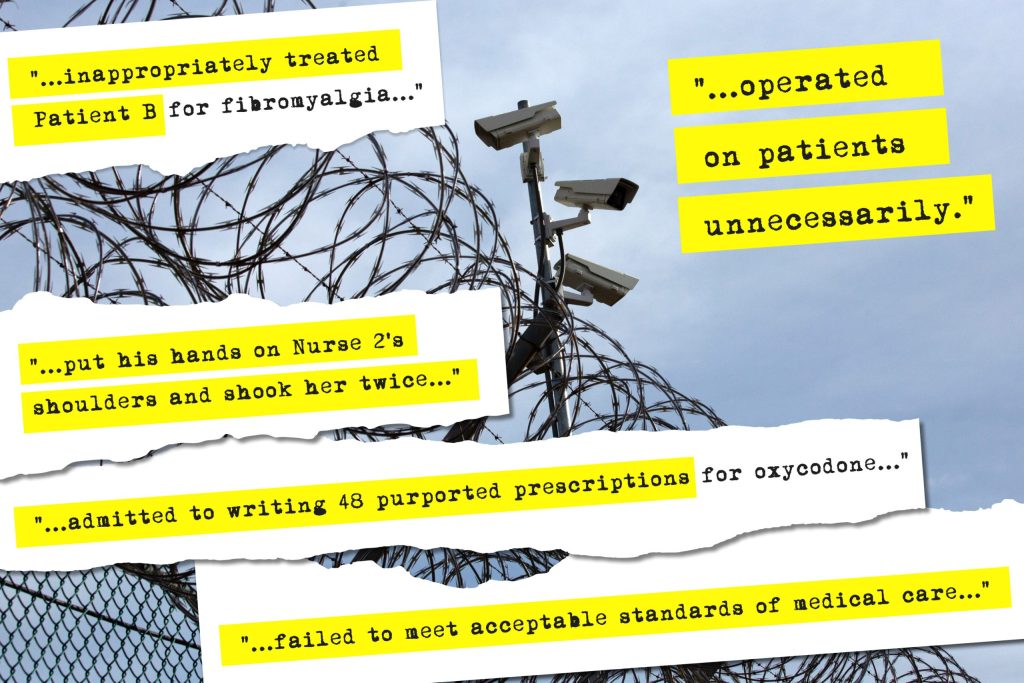

A third, a cardio-vascular and thoracic surgeon, was charged by New York State’s Office of Medical Conduct with botching 10 surgeries in four years — cutting into a patient’s chest to treat an inoperable lesion and needlessly carrying out extensive, medically inappropriate procedures.

Common to all the doctors is one of their most recent places of employment: the New York state prison system.

They are among 10 physicians identified by THE CITY who at some point since 2021 made up a disproportionate number of the system’s full-time core of doctors, despite being sanctioned for horrific mistakes and other professional abuses.

During that time, they have comprised as much as 10% or more of the system’s full-time core of physicians, a figure 20 times higher than the presence of such doctors in the state as a whole.

Some were hired by the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision even after serving lengthy probationary sentences meted out by the state’s Board for Professional Medical Conduct.

They include doctors like Christopher Wright, health services director at Five Points Correctional Facility, which has a capacity of 1,500 inmates, who is named in two pending suits challenging prisoners’ medical care.

The corrections department brought him on after he did not contest charges that he violated regulations covering the prescription of potentially addictive drugs and served a three-year probation during which he was monitored by another doctor.

Other physicians were sanctioned by the board for transgressions that took place after being hired by the prison system. Those involved private clients and, in one case, an incarcerated person.

Among them is Dr. Qutubuddin Dar, a physician who, in a March 2016 consent agreement with the board, admitted to draining the wrong side of a patient’s chest. In the agreement, he also acknowledged that in five examinations over seven months he failed to properly treat, or even diagnose, lung cancer in a 71-year-old private patient who had smoked for 50 years. The patient died in June 2013 after the cancer spread to her brain.

Also among them is Dr. David Dinello, who was not only retained by the state Correction Department after being barred from working in hospital emergency rooms in New York, but promoted to head medical operations in two of the departments’ five regions.

He then wrote the protocols for a system-wide program that was supposed to cut off addictive drugs to prisoners faking illnesses. The initiative, abandoned by DOCCS after four years, provoked a torrent of accusations that prescriptions were also denied to prisoners who legitimately needed medications for pain and longstanding conditions.

An Aching System

The prevalence of these doctors is symptomatic of medical issues that for decades have beset a sprawling system that serves 32,000 inmates in 44 locations stretching to the Canadian border.

Prisoners often point to medical care as one of their biggest grievances, according to advocates.

The Legal Aid Society, the city’s largest public defender organization, has a staff of three whose sole job is to field medical complaints and assess what can be done about them.

“Inmates during my stay generally tried to avoid going to the doctor because when they go whatever is bothering isn’t addressed,” said Steven Jacks, a former prisoner who is suing the department over alleged poor treatment.

“The doctors would try to convince the inmates that what they are complaining about isn’t authentic,” he added. “The word they’d use is ‘malingering.’”

New York state prisons have a gaping need for nurses and doctors — particularly specialists in a range of illnesses affecting a disproportionately sick population.

But attracting medical professionals to remote upstate areas is a challenge that’s only compounded when the local prison is doing the hiring. It’s a predicament faced by correctional systems across the country.

“The truth is DOCCS is desperate to hire doctors,” said Amy Agnew, a lawyer who filed an ongoing class action suit on behalf of approximately 3,000 inmates who claim that Dinello’s drug program affected their care. “They can’t attract them. So they take what they can get. And what they can get is often what other people don’t want.”

As of last month, the system, which employs 68 full-time physicians, listed seven openings for doctors and more than 300 for nurses.

In 2023, according to THE CITY’s analysis of two public databases that track medical discipline, only 0.5% of New York’s doctors overall were disciplined for failing to meet basic medical standards.

Inside the prison system, the analysis found the rate to be at least 20 times higher at its peak for doctors listed on the most available prison payrolls, which cover 2021 through 2023.

“That number is much higher than normal and much higher than can be explained by coincidence,” said Dr. John Alexander Harris, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh Medical School who authored a paper that evaluated the frequency of license infractions nationally.

Thomas Mailey, DOCCS’s prime spokesman, acknowledged the department’s recruiting issues and defended its hiring policies. “DOCCS is facing the same challenges as many hospitals and medical facilities across the country,” he said, adding that it “aggressively” seeks job candidates at job fairs and colleges and online.

“DOCCS has occasionally hired a physician with a restriction on their medical license, and those physicians are monitored closely and re-assessed frequently,” he said. “They are only kept at DOCCS if their clinical and professional work is competent, and the restriction is temporary and eventually lifted.”

In investigating this story, THE CITY reviewed thousands of pages of legal documents and medical board records and interviewed more than 30 people. It used SeeThroughNewYork — a website operated by the Empire Center, a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank in Albany, that lists public employees — to identify prison doctors over the three most current available years, 2021 through 2023.

The roster was then cross referenced with records posted by the medical conduct office that identify doctors who have been disciplined in professional proceedings.

THE CITY also reached out to the six doctors named in the story via phone calls, text messages and emails. Dinello was the only one who responded substantively, denying all the allegations against him and asserting the legal disputes involving his drug program were a result of his diligently trying to prevent prisoners from becoming addicted to pain medication.

Doctors Judging Doctors

THE CITY’s findings were not surprising to several lawyers and patient advocates, who have long criticized state medical boards for allowing doctors who should have lost their licenses to continue to practice. The boards usually are heavily made up of doctors nominated by state and local medical societies.

“The culture of the physician world in general is deference to other physicians and is focused on second chances, remediation, taking courses,” said Carol Cronin, the executive director of Informed Patient Institute, a nonprofit that seeks to empower patients. “So generally people are given second chances, sometimes third, fourth and fifth chances.”

The New York State Department of Health’s Office of Professional Medical Conduct and the state Board for Professional Medical Conduct are responsible for investigating and adjudicating complaints against physicians.

The medical conduct office probes complaints about doctors and other medical professionals and based on these investigations, the board issues hundreds of sanctions a year, state Health Department records show.

A review by THE CITY of the disciplinary system’s record concerning doctors who have worked in the prison system traces a 25-year pattern in which practitioners are sanctioned for serious professional lapses but allowed to retain their licenses, creating a path to steady work with DOCCS.

Often physicians accused of repeated instances of medical misconduct, incompetence and negligence have been allowed to plead to as little as a single charge. In consent agreements, the medical board regularly meted out lengthy license suspensions but within a sentence replaced them entirely or in large part with probations.

Under these, doctors can keep working under some form of supervision for a period after which they can practice without a monitor.

In response to questions about this pattern, Cadence Acquaviva, a spokesperson for the state Health Department, said that her department “takes professional misconduct seriously and acts appropriately to protect the health and safety of patients.”

She declined to comment on specific allegations.

‘Negligent’, ‘Incompetent’ — but Hireable

The history of one physician shows how serious past misconduct was no obstacle to a prison job. In 2000, the board found Dr. Mark Chalom guilty of negligence, incompetence and moral unfitness as a doctor after holding him culpable for cutting off half a baby’s left index finger during a delivery and, in separate incidents, attacking two nurses.

In its decision, the board related how Chalom was standing at a nurses’ station when a woman described as “Nurse 1” arrived in the area.

According to the decision, which cited two witnesses, Chalom “suddenly stopped, turned around toward Nurse 1, and said, ‘And you’, and then grabbed her with one hand around the neck. She then lifted herself up to her toes and moved backward to relieve the pressure on her neck because the Respondent was hurting her.”

The second nurse gave a similar account of her experience, with both saying the attacks lasted a matter of seconds before Chalom retreated.

Beyond the nurse attacks and what it termed the “negligence and incompetence” Chalom displayed in the blundered delivery, the board committee that heard the case also found him to have acted without “the care that would be exercised by a reasonably prudent physician” in six other cases, most involving elderly patients.

The state board had the power to revoke Chalom’s license, but pointedly rejected that option as “not warranted”— underscoring the word “not”.

Its decision described the attacks as “isolated incidents” that “do not appear to be part of a continuing pattern.” It rejected the most serious charges brought against Chalom, gross negligence and gross incompetence. And it considered it significant that Chalom’s other problems took place years earlier, suggesting that they were somewhat in the rearview mirror.

The board exacted a two-year suspension that after 60 days would convert to 22-months of supervised probation and stipulated Chalom go through some retraining, a psychiatric evaluation and therapy if the evaluation determined it was needed.

“The penalty imposed herein is designed to affirm the Hearing Committee’s disapproval of the Respondent’s conduct while imposing a fair punishment and offering sufficient protection to the public,” it wrote.

Chalom went on to work in the prison system for many years, and was listed in SeeThroughNY as earning $151,033 at two prisons in 2021 and making a lesser amount the following year.

During his tenure, he was brought before the medical board again, this time on charges involving his treatment in 2011 of a prisoner at Riverview Correctional Facility in Ogdensburg. The patient had a painful, expanding lump on his neck that Chalom was accused of failing to diagnose or treat. He was also charged with not referring him to a specialist as was appropriate.

The inmate’s name and the outcome of the treatment are not described in public records, but when the case was resolved in March 2015, the board again placed Chalom on probation for three years — bringing to six the years required monitoring— and ordered to undergo further medical education.

Chalom did not respond to several requests for comment. Mailey, the DOCCS spokesperson, declined to discuss Chalom’s tenure, saying the department does not comment on employees who leave the system.

Repeated Pattern

Chalom’s treatment by medical authorities was not a one-off.

Back in 1997, Dr. Manuel Palao, a cardio-vascular and thoracic surgeon who was cited for errors in 10 operations in a four-year period, signed a consent agreement citing him for “incompetence on more than one occasion.” He retained his license nonetheless.

Palao was hit with a five-year suspension that was stayed and then immediately reduced to five years probation during which he could continue his surgery as long as it was pre-approved by a monitor. He was also required to undertake 60 credit hours a year of professional education.

Subsequently, Palao has had a long tenure with DOCCS, earning $227,378 while serving in Cape Vincent Correctional Facility in 2023. He did not respond to requests for comment from THE CITY.

In November 2018, with the illicit prescription of medications by pain management doctors a national scandal, Dr. John Ricciardelli was convicted of a federal felony after admitting to writing 48 oxycodone prescriptions with no medical justification. He cooperated with law enforcement officials and was spared a prison sentence, instead receiving three years probation and $25,000 in fines and other penalties.

But his medical license was still on the line. Three months after his conviction, the state Health Department summarily suspended his license and brought charges against him before the medical board. It recommended that either his license be revoked or that he be barred from prescribing medications of any kind and receive a suspension that could be reduced to probation if board members chose.

Ricciardelli pleaded for less. He hired the powerhouse law firm Abrams Fensterman, had a Catholic priest testify on his behalf, said he voluntarily counseled people on the dangers of the drugs he once illicitly prescribed and swore off pain management as a specialty.

The board was responsive. When he asked that a suspension not exceed four months, it gave him two, citing the time served under the suspension imposed by the health commissioner. Although state health officials had recommended two years of probation, the board gave him 18 months. When he requested that he not be barred from prescribing all drugs, only oxycodone and similarly addictive ones, the board agreed.

Ricciardelli earned $223,612 while serving in Elmira Correctional Facility in 2023.

He did not respond to requests seeking comment via his cell phone and email.

Rise of a Problem Doctor

No consent agreement involving a prison doctor had ramifications like those involving Dr. David Dinello.

His tenure in the state prison system began in 2006 when he started to moonlight for DOCCS while working at Auburn Community Hospital near Syracuse, according to court records.

Four years after starting his prison work, he was charged with failing to adequately evaluate three patients in the Auburn emergency room.

He pleaded guilty to a single count before the medical board in 2010 and was banned from practicing emergency medicine in New York. He was also placed on probation for three years.

In a phone interview with THE CITY, Dinello downplayed the sanction, asserting that none of the patients tied to the case died “or got worse.”

He said that his training was in internal medicine and that he only began working in the emergency department because of a doctor shortage.

“So I wouldn’t order a lot of tests,” he recalled. “So the hospital wanted me to order more and more tests.”

“I said, ‘Well, that’s not the way I trained. I can use a stethoscope in my hands and examine them.’ I don’t need to order CT scans for everybody.”

The board’s decision does not reveal the details of Dinello’s failures or their impact on his patients and the Corrections Department, citing his departure from prison employment, has refused to say if it took internal action against him after the board’s ruling.

But his climb up the system, despite being banned from the state’s emergency rooms, is well documented.

Even though court records show that he had no experience overseeing doctors caring for prisoners, he was named medical director of two of the department’s five regions.

“I was the primary in two hubs,” he told THE CITY, adding that he was the “default” supervisor in two others.

That put him in charge of oversight and supervision of doctors, nurses, physical therapists and other clinical providers. He also served as chair of the system’s influential Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee and, in 2017, played a key role in creating the department’s controversial Medications With Abuse Potential (MWAP) policy.

The initiative required rank-and-file doctors to get permission from supervising doctors before prescribing a host of medications that could potentially be abused. This addressed a concern in all prison systems because of the number of incarcerated people with histories of addiction and the risk of drugs being bartered.

Yet, complaints soon mounted that the MWAP policy deprived patients of needed drugs that they had often relied on for many years and it led to the pending class action lawsuit filed on behalf of approximately 3,000 people who have been incarcerated.

In his interview with THE CITY, Dinello defended the now-defunct program, arguing that pain medications had to be administered vigilantly.

“The patients at DOCCS, 85% have a history of substance abuse addiction,” he told THE CITY. “So we have a highly sensitive patient population.”

Prisoner advocates and their lawyers are “obviously going to try to paint me as a bad guy, a bad doctor,” he added. “I get that. It’s been happening for years, but that’s not the case. I cared about these patients.”

A number of these patients were in the care of a physician who fought against the program, Dr. Michael Salvana. Salvana, whose professional education included a year at Yale Medical School, served as the director of the 152-bed Walsh Regional Medical Unit in Rome, which handles many of the prison system’s most complex cases.

In meetings and emails with Dinello and other top medical officials, Salvana made his case and pleaded fruitlessly that his patients be exempted from the MWAP program. Those documents are now part of two whistleblower lawsuits brought by Salvana.

In the monthly magazine Prison Legal News, he described witnessing patients deprived of longstanding medications “in the fetal position, rocking with pain.”

His first suit, filed in 2021, provided detailed accounts of eight patients depicted as suffering the effects of medication deprivation. Their conditions included advanced colon cancer, nerve impingement on the spine, sickle cell anemia, degenerative disc disease and both HIV and epilepsy.

Aside from intense pain experienced by all his patients, Salvana said the patient with HIV and epilepsy experienced two seizures and that another inmate who was refused an emergency injection of an antipsychotic drug punched his way through a reinforced window and attacked a corrections officer.

In August 2022, Judge Brenda Sannes of Federal District Court in Syracuse ruled that part of Salvana’s initial lawsuit was duplicative and narrowed it. She has yet to rule on the merits of the suit.

She also determined that one issue he raised should have been

brought in state court, leading Salvana’s lawyers to file the second suit in state Supreme Court in Albany where it is scheduled for trial in April.

Salvana declined to talk to THE CITY.

“He does not want any statements of his at this time to affect his current pending cases,” said his lawyer, Carlo A. C. de Oliveira. “He believes that both of his lawsuits speak for themselves.”

Lawyers representing the state and Salvana have asked the judge to make a summary decision in their favor without a trial. Her decisions are pending.

The class action case against MWAP is still moving toward resolution, as well, long after the program was terminated by the state in 2021.

Asked why it was discarded, Mailey, DOCCS’s primary spokesperson, said the department was unable to answer the question “since the personnel involved are no longer employed by the department.”

Dinello left DOCCS employment within a few months of the program’s demise.

Dealing with Pain

Remaining in the system is Dr. Christopher Wright, who, as the facility health services director at Five Points Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison in upstate Romulus, supervises medical care at the facility and oversees all its nurses.

Wright was hired by the Corrections Department in 2020 although he did not contest three charges of medical misconduct before the state board and was placed on probation between 2014 and 2017. In two of the cases he was found to have either inappropriately prescribed drugs or to have failed to document his rationale for doing so, as required.

Three years after completing probation, Wright was working at Five Points, where he earned $183,136 last year.

He has been named a defendant in lawsuits filed by two formerly incarcerated men alleging poor medical care at the prison and that they were denied medications they sorely needed.

When reached by phone, Wright declined to comment on the cases or his medical board sanction, saying only, “I love my job working for the Department of Corrections.”

One of the suits was brought by Steven Jacks, who is confined to a wheelchair and suffers from chronic back pain so intense that he frequently is unable to move his legs, according to his complaint. Filed in Federal District Court in November 2023, the suit is still pending.

“Most of the time, I didn’t get undressed to go to bed because I couldn’t,” he told THE CITY. “I never tied my shoes. I couldn’t bend down. I would be in underwear that I had worn for weeks at a time.”

A prison doctor in 2007 prescribed Baclofen, a muscle relaxant, and Lyrica, often used to treat nerve pain, the court complaint alleges.

But the Lyrica prescription was suddenly yanked when the MWAP policy was implemented on Jan. 3, 2017, according to his prison medical file.

Jacks, 69, who also suffers from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease (COPD), said he begged multiple prison doctors to be put back on Lyrica, to no avail.

In September 2019, Jacks joined the class action lawsuit MWAP. The next year, Wright came on board at the prison system and conducted a reassessment of some patients including Jacks, according to his independent legal case against DOCCS.

Wright also defended the MWAP policy in emails cited in the lawsuit to Dinello and Dr. Carol Moores, the department’s chief medical officer.

“As a locally trained physician from the Rochester area and with some 27 years practicing as a physician, it is my opinion that the MWAP prescribing policy makes sense and operates in the best interest of the health of the inmates I supervise,” he emailed Moores.

Jacks told THE CITY that Wright initially refused to put him back on Lyrica and never examined him in person.

Eventually Wright put him back on the medication but Jacks had to wait six months for the reinstatement.

A Complicated Life

Aditep White, who like Jacks has been released from custody, is the other prisoner who brought a lawsuit naming Wright. His complicated life and medical history are indicative of those of many others behind prison walls.

White was about 8 and living in a remote area of Thailand when he was adopted by a couple from upstate New York.

He suffered from cognitive delays due to the lack of “ability and education and resources” in the villages he grew up in, according to his mother Christine Michael, a retired college professor.

Describing him as resilient and “very artistic, musical and social,” she also detailed how he has struggled with post traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and a type of schizoaffective disorder.

His life took a dire turn in 2017 when he was charged with possessing an obscene image on a cellphone and arson in the fourth degree, creating a fire that damaged an apartment building in Glens Falls.

He pled guilty later that year and was sentenced to 1 ½ to 3 years in prison, court records show.

An account of what allegedly happened next emerges in his suit, which was filed in the federal court covering New York’s Western District as well as a second related suit in Syracuse’s Court of Claims.

They rely on a wealth of sealed prison medical records referenced in his legal complaint. The account is augmented by other medical records left unsealed that were reviewed by THE CITY.

The federal suit, which was filed in August 2022, claims White began to suffer from extreme spasms, debilitating pain, incontinence and other conditions and was barely able to move on his own.

On July 21, 2020, his entire body was spasming so badly he fell out of his bed, it contends, but “a nurse could not obtain his vital signs because his muscles were so tight.”

In the face of this, the suit alleges his care was lacking in the extreme, with prison staff, who report to Wright, canceling his prescriptions, including pain medications, and refusing other requests including ones for adult diapers and permission to eat in his cell because he couldn’t walk to the main mess hall.

“Mr. White,” the complaint alleges, “was consistently left to sit in his own urine and feces in his wheelchair while spasming uncontrollably.”

In an interview, his mother described a constantly deteriorating situation that no one seemed attentive to. “There are days when you are just hoping to hear his voice so that you know he’s alive after his sharing that he doesn’t think he can go on anymore,” she said.

Representing Wright as a state employee, the state Attorney General’s office hired Dr. Neel Mehta, who specializes in chronic pain treatment at Weill Cornell Medical Center, to review two tranches of relevant medical documentation. He defended White’s treatment, finding that it was attentive despite being complicated by the suspicions of medical staff at Five Points and prior institutions that he at times exaggerated his conditions and “malingering.”

“It is my opinion that the defendants provided adequate treatment to Mr. White without any delay in treatment, including treatment of Mr. White’s chronic pain and spasms, as well as adequately addressing Mr. White’s mobility issues by providing reasonable accommodations,” he wrote.

Agnew, who is handling White’s suit as well as the class action case, retained another expert, Dr. Adam Carinci, the Division Chief of Pain Management at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Carinci visited Five Points in September 2020 to examine White and several other patients. He testified in the Court of Claims trial in Syracuse that he would never be able to forget what he saw when he inspected White.

“”It was really one of the most startling displays that I’ve seen of a patient,” he testified.

White, he recalled, was wheeled into a room, slumped over, completely disheveled and intermittently convulsing. He couldn’t speak and “had an odor to him that was clearly incontinence,” Carinci added.

‘No Major Medical Problems’

At one point, Wright thought White could use more help, according to an internal correspondence reviewed by THE CITY. He noted that White “likely will benefit from … seeing an expert in movement disorders.”

“But,” the complaint contends, “he did nothing to help Mr. White’s immediate pain and suffering, nor did he input a referral for such an expert.”

White was eventually sent to SUNY Upstate University Hospital in Syracuse, where, it was hoped, experts could figure out what was at the bottom of his deterioration.

Dr. Laura Simionescu, a neurologist at SUNY, testified during the Court of Claims trial that White’s rapid decline and loss of motor skills and bodily function were related to an unknown degenerative neurological disease.

After his release, a neurology team at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire found some of the genetic markers of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, an ailment of the nervous system.

The assessment Wright delivered in testimony this April in Syracuse, however, reached a different conclusion.

“So Aditep White had no major medical problems,” Wright testified during the Court of Claims trial in Syracuse in April 2024. “He had no physical health issues. His major problem was mental health issues.”

A Small Village

Before White’s release later that year, his parents bought a double-wide trailer on an acre of land near Lake George. They put in handrails and adjusted the widths of the doors to make space for his wheelchair.

Confined to bed and recently placed on a feeding tube, he is now close to death, according to his mother.

“He wants to keep as much independence as he can,” she said, describing how health aides, friends, and people from church routinely stop by, many with food.

“We are trying our best to preserve what in life can give joy and meaning right now,” she said.

But thoughts still eat away at her about her son’s treatment in prison, and the similar care she is certain others experience.

“I mean, these are human beings,” she said. “Yeah, maybe they’ve made some poor decisions, but you don’t treat any human being on earth that way. Leave them lying on a cement floor in their own shit.”

Additional reporting by Safiyah Riddle.

If you have information you want to share about the medical treatment of incarcerated people, please contact Reuven Blau at rblau@thecity.nyc.