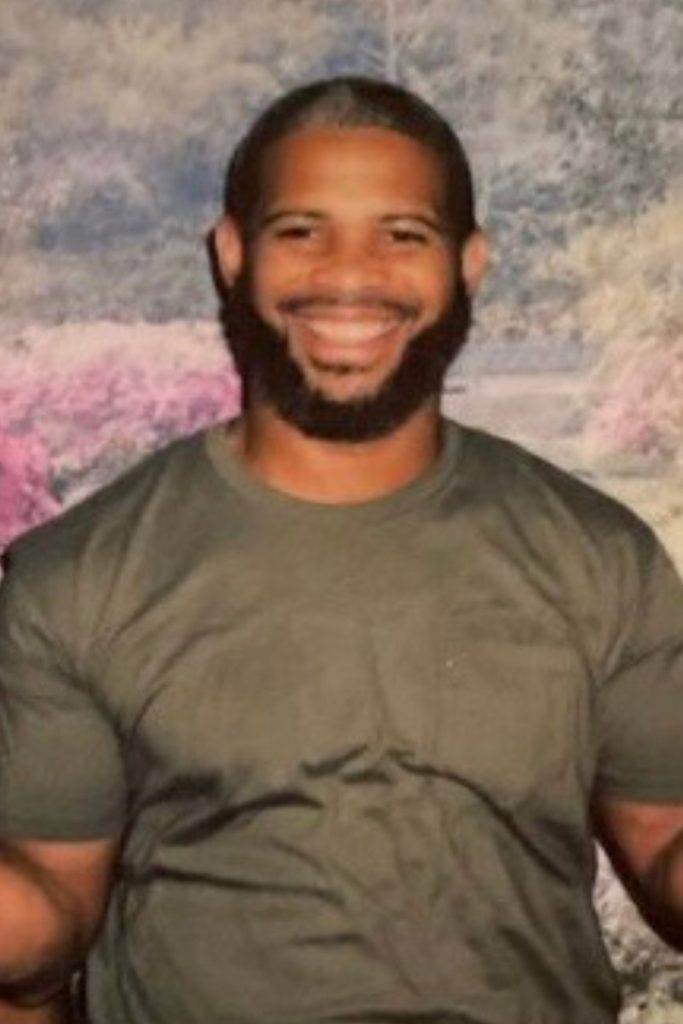

Tayden Townsley, 47, hopes this is the final holiday season he spends behind bars.

Townsley was 19 years old when he fatally shot a 16-year-old member of a rival drug gang and wounded another in a Sullivan County apartment on July 1, 1994.

He was sentenced to 37 and a half years to life for the crime and won’t be eligible for a parole hearing until 2037, when he’ll be 60.

After over 28 years in prison, he’s asking Gov. Kathy Hochul for clemency.

“I know clemency is rarely granted and only given in the most special of circumstances,” Townsley wrote in his 224-page application.

He asked the governor to view him not as the “misguided adolescent” he used to be “but the man I have become.”

Hoping for More

Townsley’s is one of at least 1,500 applications from state prisoners seeking leniency from Hochul this year, according to Steve Zeidman, director of the Criminal Defense Clinic at the CUNY School of Law.

Since taking office in August 2021, Hochul has granted clemency — in the form of a sentence commutation — to 16 people.

Five months after becoming governor, she vowed to reform the clemency process and issue releases on an ongoing basis throughout the year.

All told, she has commuted 17 sentences since taking office. That includes one in 2021, four in 2022, nine in 2023 and three this year so far.

“My hope is that she will do much more,” said Zeidman, who is representing Townsley.

But he’s frustrated that the number of clemencies is down this year.

“Why the decrease when, if anything, she’s getting more and more robust applications?” he asked. “You would have thought numbers would go up.”

Avi Small, a spokesperson for Hochul, declined to comment on the overall drop. He cited a statement the government made when announcing the latest release on Friday.

“Upon taking office, I implemented a series of reforms to bring additional transparency and accountability to the clemency process,” Hochul said in the press release. “I will continue working with law enforcement, victims’ rights groups, prosecutors, reform advocates and all stakeholders to ensure this process is operationalized responsibly.”

Hochul’s decrease in clemency comes as President Biden on Monday commuted the sentences of 37 of 40 federal death row inmates to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Earlier this month, Biden also commuted the sentences of close to 1,500 people who were put on home confinement during the pandemic. Additionally, he pardoned 39 people convicted of non-violent crimes.

As for Townsley, Zeidman and other supporters argue that over nearly three decades in prison he has transformed himself.

Initially, life behind bars was a challenge for the Brooklyn native. He got slapped with multiple disciplinary tickets for disturbances and fights over the first eight years.

He hit rock bottom after fighting with three correction officers in 2004, according to his clemency petition. The fight led to new criminal charges and an additional five years on his sentence.

“Until that moment, he had seen himself as a victim who was being targeted by the system,” his application says.

He vowed to become a “force for good” while serving out the rest of his sentence.

Among his accomplishments are completing a two-year paralegal course, working in the law library for six years and taking vocational classes in masonry, barbering, custodial maintenance, general business and machine operation.

“He has been an incredible positive force during his incarceration, resolving conflict, improving himself and supporting others to build safer and healthier communities,” his legal team wrote in his clemency application.

From Abuse to Murder

Townsley was part of a large family: the eighth of his father’s 13 children and the eldest of his mother’s five.

He was a talented student and did so well his third grade teacher suggested he skip a year, according to his clemency application.

But his life took a turn for the worse when he was 10, and the crack epidemic hit his family hard.

“Almost overnight, in addition to his parents, his cousins, aunts, uncles and neighbors were using,” the clemency filing says.

Townsley was forced to become a caretaker for his younger siblings, but he struggled in that role and got into a lot of fights with them, according to his application.

His father was physically abusive, even before his addiction, and the constant violence at home taught him all the wrong lessons on how to adjudicate disputes, the clemency application alleges.

Between the ages of five and eight, he was also sexually abused by two relatives and a family friend, the application alleges, but he didn’t understand it was abuse and never told anyone, his clemency report says.

The family was also extremely poor. “The Townsleys were unhoused and unfed at various points while Tayden was growing up,” the clemency application says.

When he was 16, he started “muling,” moving drugs between New York City and Sullivan County for extra cash. He was arrested for drug possession and sentenced to three years of probation in 1992, court records show.

“After his arrest, however, he left the drug trade and focused on legitimate sources of income for himself and his family, starting at the paper plate factory and reselling clothes while attending high school,” his clemency application says.

But he got back into the drug trade after his graduation when his cousin and brother were shot and killed within five months of each other, the filing says.

Townsley himself was shot in the knee nine months later during a feud likely tied to one of his brothers.

“He became deeply angry about his situation, but grateful that the bullet had hit him instead of one of his brothers,” the application says. “He also became fiercely protective of his

siblings and constantly afraid that they would fall victim to the violence that surrounded them.”

On the day of his fatal shooting, Townsley brought his little brother, Salih, to Sullivan County to move a shipment of drugs and visit his girlfriend.

What transpired inside the apartment where Townsley fatally shot 16-year-old Lynell James and wounded Johmar Brangan remains in dispute.

During his trial, Townsley denied shooting James and argued he was innocent.

He has since said that James threatened his younger brother after they argued over a previous dispute.

Brangan then tried to push the door open and had a gun in his hand, according to Townsley, who shot at him through the door.

THE CITY was unable to reach family members of James or Brangan himself. The Sullivan County District Attorney, Brian Contay, was also not immediately available for comment.

But Supporters of the push for Townsley’s clemency say he’s a changed man.

“During his incarceration, Townsley has committed himself to understanding how his traumas affected his decision-making and led him to take another’s life,” his clemency application says.

Before his conviction, Townsley was offered a plea deal of 15 years to life, according to his legal team.

But he fought the case and took it to trial.

His lawyers contend that he shouldn’t face a “trial tax” since the district attorney long ago decided a far shorter sentence was appropriate.

Townsley also has some unique backers: several correction officers.

In May 2015, a group of approximately 25 incarcerated men launched a protest demonstration in Green Haven Correctional Facility. Townsley talked the group down and de-escalated a heated moment, according to a “Commendable Behavior Report” filed by a correction officer on duty at the time.

In 2017, his former defense lawyer, Joel Rudin, wrote to former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, asking for mercy.

“It is a tragedy that a man was killed,” Rudin said. “It is a tragedy that a totally different individual is still in prison for that crime committed so many years ago when he was much younger.”

“Nobody can bring back the victim of the crime,” he added, “but it is still possible to save the worthwhile human being that Tayden Townsley is today.”