Report urges $6.5 trillion annual investment in climate action by 2030 to meet targets and avoid future costs.

Countries need to invest more than $6 trillion per year by 2030 to tackle the effects of climate change or risk having to pay more in the future, according to report by an independent panel of experts at a United Nations climate summit.

“Investments in all areas of climate action must increase across all economies,” said the report published on Thursday by the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG) at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan.

The experts put the figure at $6.5 trillion to meet climate targets in advanced economies, as well as China and developing countries, and said any shortfall “will place added pressure on the years that follow, creating a steeper and potentially more costly path to climate stability”.

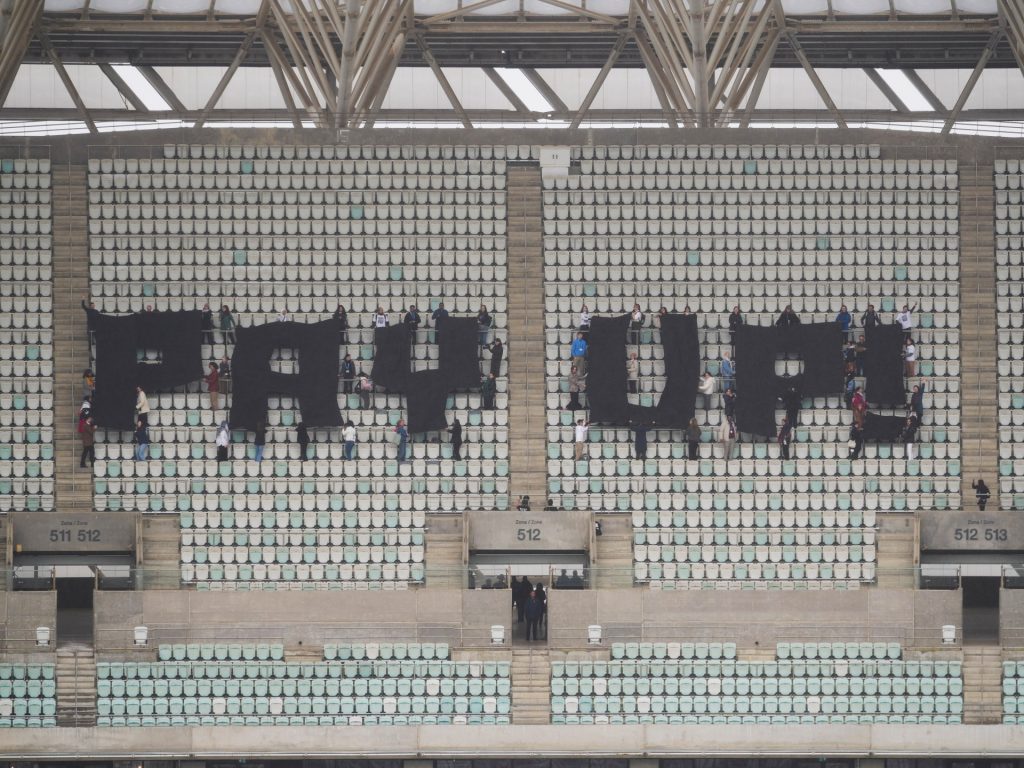

Climate finance is a central focus of the summit, whose success is likely to be judged on whether nations can agree to a new target for how much richer nations, development lenders and the private sector must provide each year to developing countries to finance climate action.

A previous goal of $100bn per year, which expires in 2025, was met two years late in 2022, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said earlier this year, although much of it was in the form of loans rather than grants, something recipient countries say needs to change.

“Parties must remember that the clock is ticking,” COP29 lead negotiator Yalchin Rafiyev told a news conference. “They must use this precious time to talk to each other directly and take ownership of building bridging solutions.”

Donald Trump’s re-election has raised doubts of the United States’ future role in climate talks. The likely withdrawal of the US from any future funding deal has overshadowed the discussions, raising pressure on delegates to find other ways to secure the needed funds.

But US climate envoy John Podesta called on governments to believe in Washington’s clean energy economy, saying Trump can slow but not stop its climate change pledges.

Some negotiators said the latest text on finance was too long to work with, and they were waiting for a slimmed-down version before talks to hammer out a deal could begin.

Any agreement is likely to be hard fought given a reluctance among many Western governments – on the hook to contribute since the Paris Agreement in 2015 – to give more unless countries, including China, agree to join them.

Countries are deeply divided over who should pay what and how much, which needs to be resolved for a deal to be reached by November 22, when the summit ends.