Four ex-Michigan football players filed a class action lawsuit against the NCAA and Big Ten Network on Tuesday. They allege the conglomerates “wrongfully and unlawfully denied” them an opportunity to profit off their names, images and likenesses. ESPN’s Jake Trotter was the first to report the lawsuit.

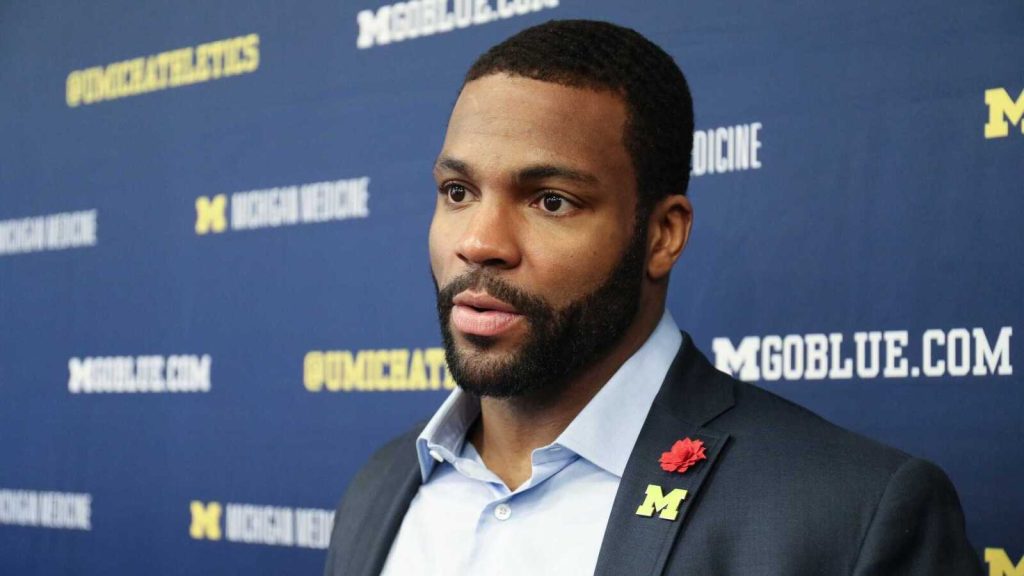

The plaintiffs include former Wolverines quarterback Denard Robinson and wide receiver Braylon Edwards, who are seeking $50 million in damages.

Their lawsuit claims the NCAA and Big Ten Network “systematically exploited these iconic moments” the players created while at the school, referencing big plays the players were a part of with the football team.

Robinson and Edwards filed the suit on behalf of players who were a part of the football program before 2016.

What does this new lawsuit mean for the NCAA’s NIL settlement?

Starting in 2021, student-athletes have been able to profit from NIL, and in May, the NCAA, the power conferences and their attorneys settled three major antitrust suits to the tune of $2.7 billion in damages. That settlement is currently on hold pending approval of revisions from a federal judge.

The NCAA did not comment to ESPN about Robinson and Edwards’ lawsuit but it could certainly complicate things currently ongoing with the antitrust settlement.

According to the original settlement agreement, any college athlete who played from 2016 onward is eligible for damages. However, 2016 is the cutoff due to the statute of limitations in the antitrust suits filed in 2020.

So, does this new lawsuit even have a chance?

Despite the 2016 cutoff in the NCAA’s antitrust settlement, the lawyers representing Robinson and Edwards’ class say they will still fight for their clients.

“The NCAA knew for decades that preventing players from monetizing the one thing of value they have — their name — was wrong and unlawful,” Jim Acho, the plaintiffs’ attorney, told ESPN Tuesday. “Today they recognize that players should have that right. But what about all the past players who were unlawfully denied that right? The money made off those players’ backs was in the hundreds of millions. … The players never saw a dime … We are here to right that wrong.”

Acho will have to prove to the court that even though the statute of limitations only reaches as far back as 2016, it must rule that deadline as arbitrary, and athletes before it are entitled to their slice of profits.

However, that case may be tough to convince as the defense could easily argue “When is the cutoff? Are student-athletes as far back as the NCAA’s creation (1906) entitled? What about as far back as the start of amateurism in college sports?”

The financial ramifications of such a decision could ultimately bankrupt the NCAA, the conferences and their media partners — potentially destroying college athletics altogether or creating a vacuum where private enterprise picks up the pieces and students truly become employees.