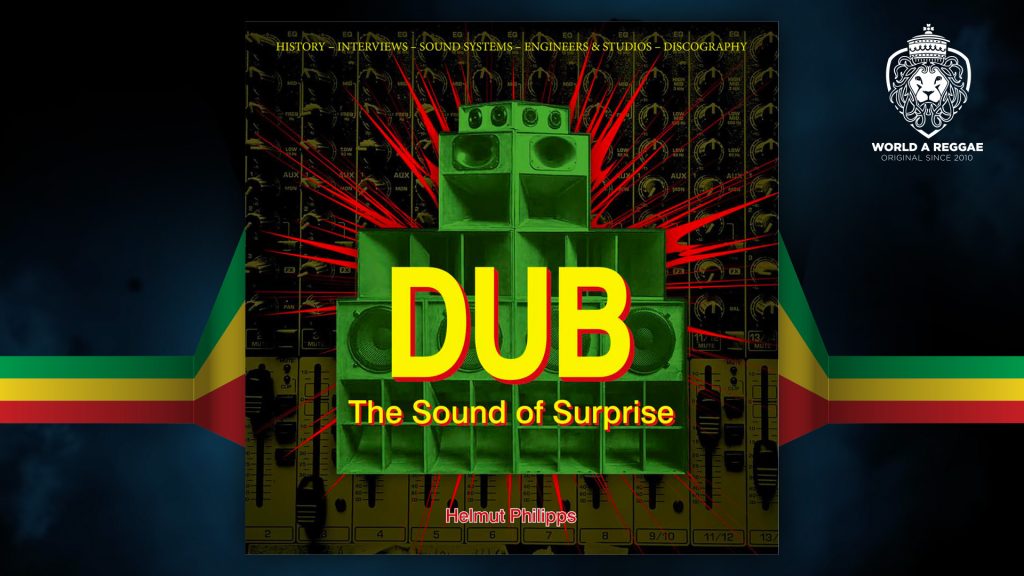

Earlier we gave you a heads up on the release of “Dub: The Sound of Surprise by Helmut Philipps“.

To follow up on this post we would like to share this review by author, documentary producer, and reggae DJ, David Katz.

In this engaging and beautifully laid-out hardback, Helmut Philipps has broken new ground in dub research, going deeper than previous explorations of the form. Philipps’ love for and understanding of what dub is and why it is important is clearly evidenced on every page of this absorbing work, which is perfectly paced and divided into easy absorbed chapters. Careful translation by Ursula ‘Munchy’ Munch has helped with readability and time and care has been taken with the layout too, the colour full-page photographs of Jamaican recording studios, European sound systems and reprints of vintage album covers adding visual pizazz, bringing better to life the music detailed in its pages. I found the book to be a page-turner full of revelations that is informing my own work and recommend it highly to all dub lovers and anyone curious about the vital reggae subgenre that has arguably had the greatest impact of all.

In the introduction, Philipps explains that the work is the expanded English counterpart to his acclaimed book Dub Konferenz: 50 Jahre Dub aus Jamaika, published in Germany in 2022, here with previously unpublished material, including testimony from Roots Radics drummer Style Scott and an analysis of US dub practitioners. A prologue helps us to understand the arrival of dub in the early 1970s and the related deejay form as offshoots of sound system culture, as well as the subsequent waxing and waning of dub’s status in its homeland.

The meat of the text begins with an exploration of the work of Sylvan Morris, illuminated by testimony from Morris about his days at Studio One, Harry J, and West Indies Records Limited (later known as Dynamic Sounds). Following an investigation of the first dub LPs, Clive Chin recalls the particulars of Java Java Java Java and Randy’s Dub, and in the King Tubby: Genius and Myth section, Philipps tries to unpack what King Tubby actually achieved at his legendary Waterhouse dub factory, as well as how he achieved it, and although he busts plenty of myths along the way, there are some questionable assertions by Philipps about the equipment used therein. Nevertheless, there is plenty of food for thought in this crucial segment and the memories of broadcaster David Rodigan, producer Bunny Lee and engineers Pat Kelly and Leroy ‘Fatman’ Thompson add further insights into Tubby’s inscrutable character and working methods.

Then we’re onto Treasure Isle engineer Errol Brown, Ernest Hoo-Kim, Barnabas and Soljie at Channel One, and Linval Thompson as a primary dub exporter; the triumphs and trials of Scientist are relayed with thoughtful nuance, as is the rise of King Jammy and the semi-dub, semi-instrumental adventures of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry at the Black Ark. The ‘Dub In The UK’ segment takes in Dennis Bovell, Adrian Sherwood, Mad Professor and unsung hero Mark Lusardi, and after Style Scott’s illuminating testimony, which forms a bridge between Jamaican dub and new dub styles being made in the UK, Philipps moves on to North America, zeroing in on the work of New York-born, Brazil-based Victor Rice and St Croix-born Tippy I Grade. Then, the tongue-in-cheek epilogue titled ‘an Echo Doesn’t Make It Dub,’ Philipps looks at more recent developments in Jamaica and overseas, lamenting that what is now termed dub is very far from what the form originally represented. A discography at the end is another helpful addition and any work that is not Philipps’ own is correctly sourced.

As with every other book about reggae, including my own, there are a few minor factual errors here and there, but they don’t really detract from the quality of the work. Additionally, some readers may disagree with Philipps’ critical reading of Mento, his negation of any relation between dub and an ancestral African path, as well as the clear line Philipps draws between classical dub and its steppers offshoot; readers will simply have to make their own conclusions about the merits of such assertions.

If you’re a dub head like me, Dub: The Sound Of Surprise is simply required reading, but even if you know nothing about the form, you can pick up this book and be wowed by its contents. There is tons to discover in this substantial and worthy tome, and I thank Helmut Philipps wholeheartedly for writing it. – David Katz.