At about 10 p.m. on Oct. 15, a black Chevy Equinox pulled up to a ranch house in the southern New Jersey city of Bridgeton. A group of men in ski masks hopped out and headed for the front door. A sign beside it featured a single word: Blessed.

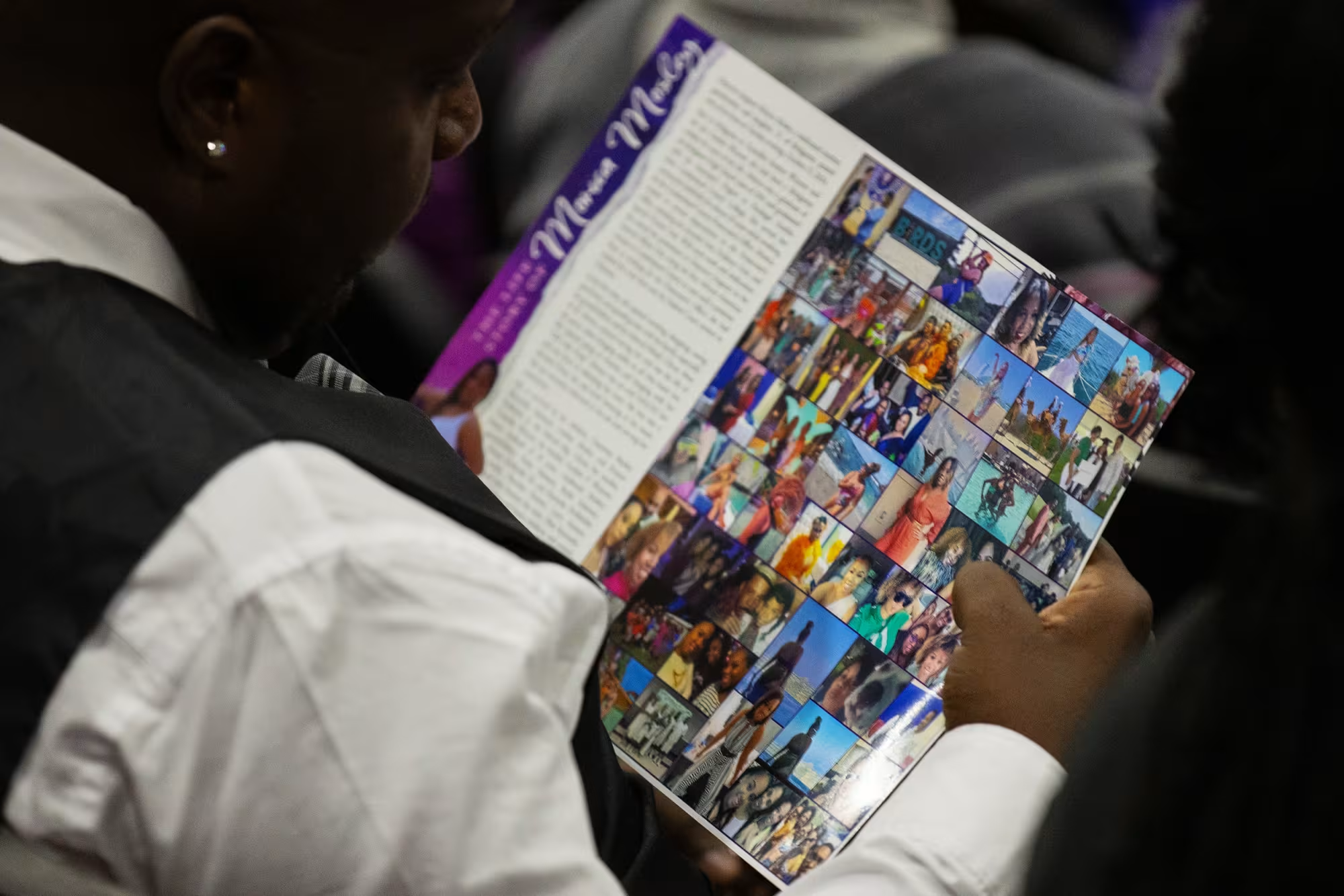

The home belonged to Detective Sgt. Monica Mosley, a 15-year veteran of the Cumberland County Prosecutor’s Office. Mosley worked in internal affairs, where she was believed to be the first Black female sergeant in the history of the unit. She was also a mother and grandmother, with an infectious laugh and two grandchildren on whom she doted.

Mosley, 51, was in her bedroom when the men kicked in her front door and rushed down the hallway, prosecutors say. A gunbattle broke out almost instantly.

Mosley squeezed off three rounds with her service revolver, striking one of the men in the right shoulder. But a bullet hit her in the right knee, according to prosecutors, likely knocking her to the ground.

A second bullet struck her left wrist. And then came the fatal round: One of the men shot her in the back of the head execution-style, prosecutors say.

Mosley was later pronounced dead at the scene. Her killers, after jumping back into the SUV, vanished into the night.

“It’s unfathomable,” said Alexis Pulman, a retired lieutenant who worked closely with Mosley. “Why her? And why in this fashion?”

The killing of a law enforcement officer in their own home by someone other than a romantic partner or family member is highly unusual. While the FBI tracks the number of officers killed in the line of duty each year, there is no known available data on those whose lives are taken in circumstances like that of Mosley’s slaying.

“Execution-style murders of police officers just don’t really happen,” said Dennis Kenney, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. “Off the top of my head, I can’t think of this ever happening in the U.S.”

The murder reverberated across the state, drawing condemnation from New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy and anguished tributes from Mosley’s law enforcement colleagues. She was a beloved figure in her office and in the wider community of Bridgeton, where she was born and had lived for most of her life.

“She was this shining light,” Pulman said. “She tried to make beauty out of the ugly in life.”

About two weeks after Mosley’s killing, three men with criminal records were arrested on murder charges in connection with the crime. A woman who was dating one of the men was also arrested and accused of trying to cover up evidence. And in early November, a fourth man was charged in Mosley’s murder. He had been released from state prison only six weeks earlier.

There is no indication yet that Mosley was targeted because of her job or any specific case that she investigated, according to a law enforcement source familiar with the investigation. No links, direct or indirect, have been found between the four men and Mosley. Their motive remains a mystery, leaving her grief-stricken family, friends and former colleagues grasping for answers.

Special Victims to Internal Affairs

Situated in a rural swath of New Jersey, Bridgeton lies about 40 miles south of Philadelphia and 50 miles northwest of Cape May, the southernmost tip of the state. With a population of roughly 25,000, it is the county seat and third largest city in Cumberland County, a vast area of farmland and green space along the Delaware Bay.

Once a thriving industrial community full of grand Victorian-style homes, the city went into decline in the 1980s when its glass and textile plants began shutting down.

Bridgeton is now a racially diverse, working-class enclave that is not immune to violent crime. There were 15 murders in 2023, and 15 so far in 2024, according to the Cumberland County Prosecutor’s Office.

But “home invasions are rare,” the top prosecutor, Jennifer Webb-McRae, said in an email. “Home invasion homicides are rarer.”

Mosley joined the county prosecutor’s office as a paralegal in 2006. A sergeant saw something special in her and urged Mosley to go for a detective role when some positions opened up in 2009. But with no law enforcement experience, Mosley was required to complete the 20-week, boot camp-style police academy course, which was no easy feat for a woman who was older and had far more responsibilities at home than the typical new hire.

“Neither one of us were runners, and neither one of us were in our 20s,” recalled Michelle Urgo, who was in the Division of Criminal Justice Academy at the same time as Mosley. “We both had husbands at home and children at home, but we pushed each other to get through it.”

The pair went on to become close friends.

“She made people feel like you were automatically part of her family,” Urgo said. “And once you were in that circle with her, that didn’t change. Ever.”

That ability to connect with people and gain their trust helped Mosley excel as a county detective dealing with crime victims, her former colleagues said. She was also firm when she had to be and unafraid to speak her mind, they said.

Mosley saw herself as playing a vital role in safeguarding the community she held so dear.

“She loved her job,” Urgo said. “She loved it because she was making a difference.”

Pulman, the retired lieutenant who worked closely with Mosley, was so impressed with her that she recruited her to join the Special Victims Unit, which investigates sex crimes and child abuse. Years later, Pulman convinced Mosley to again join her after she moved to what is widely considered one of the least desired posts in law enforcement — the internal affairs unit.

Members of internal affairs are tasked with investigating their peers when allegations of criminal behavior are reported. In Cumberland County, it’s known as the Professional Standards Unit.

“I was fearful when I started there, and there is no doubt she was,” Pulman said. “But she embraced it fully, and I knew she would.”

Mosley worked hard but she also knew how to unwind, Pulman and others said. She loved to travel to faraway places like Thailand, cheer for her beloved Philadelphia Eagles and go out with the close group of friends she called her “old lady gang.”

“She was living her best life and traveling all over the world,” Pulman said.

Mosley was divorced with two adult daughters who had been soccer and track stars in high school, as well as twin granddaughters whom she called “the rascals.”

“Her kids and her grandchildren were her life,” said Lt. Brian McManus, who was Mosley’s supervisor in internal affairs. “She really loved talking about them.”

The weekend before the murder was a busy one for Mosley. She worked all night Saturday into Sunday morning on what McManus described as a “sensitive arrest.”

On Monday morning, she and McManus met in the office and laughed about some of the frustrating issues that had come up over the weekend. “That’s what cops do,” McManus said. “You find the silver lining and you laugh about it.”

Mosley had another challenging case on her plate. McManus told her he would take on a portion of it to relieve her load.

“She thanked me and said she really enjoyed working cases with me,” McManus recalled, his voice cracking with emotion.

At about 4:30 p.m., Mosley was preparing to go home. She was looking forward to some much needed rest after working straight through the weekend. But McManus called her just as she was about to head out the door.

“What now?” Mosley said in a light-hearted tone, according to McManus.

“We talked for just a few seconds,” he said. “I can’t even remember what it was about, but that’s the last conversation I had with her.”

A wounded man and a bogus story

Investigators got an early break in the case.

Not long after the murder, a local hospital reported that a man had arrived with a gunshot wound. The individual, identified as Nyshawn Mutcherson, 29, said he was shot in the town of Millville but investigators determined that to be a lie, according to a police affidavit.

A bullet was found on Mosley’s lawn with Mutcherson’s DNA on it, prosecutors said, and her blood was found on his sneakers.

Investigators from the neighboring Cape May County Prosecutor’s Office are handling the investigation since Mosley was employed by the prosecutor’s office in Cumberland County.

In a court hearing last month, First Assistant Prosecutor Saverio Carroccia provided a detailed timeline of the suspects’ movements on the night of the shooting. It was pieced together, he said, through surveillance videos, automated license plate readers, cellphone data and witness accounts.

The night began at the home of Cyndia Pimentel, 38, in Paulsboro, New Jersey, Carroccia said. At about 7 p.m., her boyfriend, Richard Hawkins Willis, 32, drove off in her 2012 Chevrolet Equinox and picked up three other men: Mutcherson, Byron Thomas, 35, and Jarred Brown, 31.

Just before 9:25 p.m., the vehicle was spotted pulling up to a home in Bridgeton belonging to Brown’s father. The men changed into dark clothing and left their cellphones at the house, Carroccia said, before heading to Mosley’s address. A security camera from a trailer park near Mosley’s home captured video of the Chevy passing by just before 10 p.m., the prosecutor said.

The shooting took place shortly afterward.

After Mosley was struck twice and knocked to the floor, her killer “either was behind her or walked behind her, took out the gun and shot her in the back of the head,” Carroccia told the court. “Judge, I don’t use this term lightly, but that’s called an execution.”

A witness reported seeing people running out of Mosley’s home at 10:03 p.m., Carroccia said. Surveillance cameras caught the suspects’ vehicle leaving the area and stopping at the hospital in Bridgeton, where Mutcherson was treated for his gunshot wound. It was then seen returning to the home associated with Brown, Carroccia said, and at some point was driven back to Pimentel’s house in Paulsboro, located about 30 miles north.

Three days later, Hawkins Willis and Pimentel drove about 10 miles from her home to a property associated with him in Gloucester City, Carroccia said. Investigators armed with a search warrant found latex gloves and a size 6 boot with blood on it, Carroccia said. Inside a dumpster in the driveway, they discovered a pair of floor mats, pieces of seat belt and a car part from Pimentel’s vehicle.

The Equinox was tracked to a parking garage in Philadelphia, Carroccia said, and it was Pimentel and Hawkins Willis who left it there.

The murder weapon has not been found, and it’s unclear if multiple guns were used in the crime.

Mosley’s mother, Trumiller Winrow, said that she was grateful for the quick arrests, but that she and her relatives were still in shock.

“It’s hit the family real hard,” she said in a brief interview at her home in Bridgeton.

Winrow said she had no idea why anyone would target her daughter.

“But it’s done and it’s over with, and she’s not coming back,” Winrow said. “I hope they prosecute them to the fullest.”

A motive unknown so far

The handful of current and former law enforcement officials interviewed for this article said they had no idea why anyone would target Mosley. They said it was possible that it was a random home invasion or that the suspects went to the wrong house.

Given the criminal histories of the suspects, the law enforcement officials said, it seemed unlikely that the murder was connected to her work. Brown and Mutcherson are the only ones who were previously prosecuted in Cumberland County, and there is no indication that Mosley had any involvement in their cases.

Since she started in internal affairs in 2019, she had been focused on investigating police officers and other law enforcement figures in the community.

“I’ve wracked my brain,” McManus, her internal affairs supervisor, said. “I couldn’t think of it being related to something we were working on.”

The agencies involved in the investigation – the Cape May County Prosecutor’s Office, New Jersey State Police and Bridgeton Police Department – did not respond to requests for comment.

The four male suspects have all been arrested multiple times and served prison stints. In court hearings Dec. 16, a judge ordered all four to remain behind bars pending trial. The judge, Joseph Levin, detailed their criminal histories before announcing his decision to detain them.

Thomas was released from state prison Sept. 2 after serving a five-year sentence for drug distribution. He’s been sent to prison three times in total and has been previously convicted of a range of charges including unlawful possession of a handgun, burglary and criminal mischief, Levin said.

Mutcherson was also released from state prison earlier this year, in July. He had served a three-year sentence on charges of aggravated assault on a domestic violence victim and obstruction. It was his fifth prison stint, according to the judge.

Hawkins Willis, the third suspect, was released from state prison in 2019 after receiving a five year sentence on theft and weapons charges.

Brown, the fourth suspect, was sentenced to five years in prison in April 2017 on two weapons charges, and was released in October 2021. His criminal history includes convictions for endangering the welfare of a child by sexual conduct, forgery, hindering apprehension and obstruction, according to the judge.

Lawyers for Thomas and Mutcherson declined to comment. Attorneys for Brown and Hawkins Willis did not respond to requests for comment.

Pimentel had no criminal record, but she did have a brief career in law enforcement. She worked as a police officer in Camden County from 2013 to 2015 when she resigned.

At Pimentel’s detention hearing, her lawyer emphasized that his client had no criminal history and didn’t even know the other suspects beyond her boyfriend, Hawkins Willis.

“She is truly a law-abiding citizen who happened to get involved with someone who used her car on a particular day and may have been involved in some criminal activity,” Ron Thompson said.

Carroccia, the prosecutor, argued for Pimentel to be detained, noting that she may not be safe on the outside.

“Law enforcement has received information from a confidential informant that an individual out of state was contacted to come down and take care of any and all individuals who are involved in connection with this homicide,” the prosecutor said.

The judge ultimately sided with Pimentel’s lawyer, ordering her to be released from jail ahead of trial.

A bright light

Mosley’s friends and former colleagues, meanwhile, have been struggling to reconcile the sudden and violent death of a woman who was such a bright light.

“The world lost such an incredible human,” Pulman said.

“I hope someday we get an answer,” Pulman added, referring to why she was killed. “But I still won’t get her back. None of us will.”

In the days after her death, tributes to Mosley piled up on the website of the funeral home where her memorial was held. Among the dozens of remembrances from family members and friends was a message from a mother who said that a terrible event had brought her into contact with Mosley — a crime against her 5-year-old son.

“I cannot believe ur gone,” the woman wrote. “You did not stop until you got justice for my son and you still kept in touch with us.”

The woman added: “I’ll always love you and remember u for that Sergeant Detective Mosley.”

Jonathan Dienst contributed.

This article originally appeared on NBCNews.com. Read more from NBC News: